|

| Previous | Next |

What the malignant spirit that has captured us wants is this: genocide and slavery. Literally.

* * *

Have you ever really thought about what it takes to enact genocide and slavery?

You don’t need a population to want genocide and slavery in order to enact them. You just need to convince them to accept a series of propositions that will lead them there, that make such an end first possible, then likely, and finally inevitable, even normal.

What you need are bubbles.

I suspect no society that has ever committed genocide or enacted slavery has ever let themselves see themselves for what they were. Example: most 'white' U.S. citizens, if asked, probably don’t think the United States is responsible for multiple genocides. We might if pressed admit they occurred, and even that they were very sad, perhaps even bad. But most of us reject the notion that the United States is responsible.

But we are. The United States is responsible for multiple genocides.

We’ve forgiven ourselves.

|

| Pictured: Buffalo corpses. This is what we did to a primary food source, specifically because it was a primary food source. |

It was a long time ago. That's what we say. It has no effect today.

Yet somehow we still revere our founding 'fathers.' We put them on our currency. We resist any attempt to deconstruct the mythologies we've built around them. We propose to follow their every intention to the letter. Yet most of them owned slaves and built extraordinary wealth from their labor. All participated in some way in our genocide of the native tribes who lived in this land for millennia before our country's founding. We live on that land. That wealth shaped the country in which we live.

Thus the past has no bearing on the present, except when we think it should have every bearing on the present.

We only inherit wealth in this country, not responsibility.

Nor do individuals think of themselves as evil any more than societies do. We tend to appeal our actions from our goodness, not our badness. Every society that has ever committed genocide and enslaved others has been full of good people—brave people, intelligent, well-read, who loved their children, and helped one another with good will, and gave to charity, and so on and so on and so on. So many good things. So many, it seems impossible—wicked, even—to believe bad of them.

That’s the horror of it. It’s never demons. It’s always just regular, good-hearted people. People who would help you move or change a stranger’s tire on the side of the road or bake meals for a family with a sick parent. Generous. Charitable. Kind. Brave. Well-meaning. But preferring order to justice.

Order is very good, remember. It’s important. It’s even fundamentally necessary. But sometimes order will come into conflict with justice. And what then?

If order is prioritized over justice, or if order is mistaken for justice, you will eventually begin to hear all sorts of propositions that might seem shocking, particularly to those who take as their first priority a justice grounded in love. You start to hear arguments that end, either implicitly or explicitly, with, "and that's why a lot of people unfortunately will have to die."

You wouldn’t hear people express these propositions out loud in blunt terms—not at first, anyway. You’d have to watch the society for actions taken and statements made, to see what the logical assumptions behind such actions and statements must be.

Let’s do genocide first. (This would be an unfortunate sentence to take out of context.)

If I want genocide, first I'm going to have to work on dissolving the idea that we all belong to each other—not ‘belong’ in the sense of property, but rather in the sense of relationship. There is no way what happens to you doesn’t affect me, or me to you. We create a human ecosystem from which we are fundamentally inextricable. This is true from the local level to the global. When one of us is mistreated, we are all mistreated. Injustice eventually hurts even the seeming beneficiaries.

If I want genocide, I'm going to have to dispatch this idea right away. I'll want to foster the notion that each of us is a self-created being, and our successes or our failures are the functions only of our own effort and choices. The suffering of another is entirely the business of that person, and nothing to do with you or me.

It may be necessary to expand the definition of ‘self,’ to include one’s family and friends, perhaps one’s neighborhood, or ethnicity. But eventually there will come some boundary, some impermeable delineation. At some point we must build a big beautiful wall between our specific ‘self’ and other people, and make those other people pay for it. We don’t belong to each other. Each ‘self’ is an island, complete to itself.

There are questions that come naturally, when we do not belong to one another. They are “I” questions. The ‘I’ will always include certain similar people that I mean when I say “I,” and it will always, crucially, exclude the rest.

Why should I pay for education when I don’t have children?

Why should I pay to see the hungry fed when I buy my own food?

Why should I pay to shelter the homeless when I worked hard to own my home?

Why should I pay to clean the lead from their water when my pipes run clean?

Why should I pay for the sick to receive care when I am healthy?

Why should I have to pay for prenatal care when I’m not a woman?

Why would my money go to provide relief to a country I don’t live in?

Why would I let that family from a dangerous country into my country when I am already safe?

These are the questions people ask, in a society that no longer believes that we all belong to each other.

There are few in such a society to ask: What is the price to be paid for an uneducated population? What is the price to be paid for potential ungrasped? What is the price to be paid for a nation of desperate people? What bill will come eventually due because of a country destabilized by invasion and warfare, or a population made desperate by need?

When we don’t all belong to each other, these questions don’t need to be asked. Failure and success are hermetically sealed at the individual level. The only price to be paid for a society that fails to see to everybody’s education, health, shelter, food, water, and other basic physical and spiritual needs, will be paid by the specific individual, not society. Freedom becomes a very specific and compartmentalized concept, customized to one's own particular preferences.

The only education that affects me is my own education.

The only health that affects me is my own health.

The only shelter that affects me is my own.

The only water and food that affect me are my own.

The only prosperity and the only safety that matter are my own.

And (or so I will believe if I think we do not belong to one another) if only everybody behaved that way, everyone would be fine. Because, after all, I behave that way, and I am fine. In time, certain conclusions will be impossible to avoid. If I am successful only through my own natural virtue and skill and industriousness, then others, who suffer, must logically suffer as the result of some natural fault and incompetence and sloth.

Notice that once again none of these things—education, health, shelter, water, food, wealth, prosperity—is bad; in fact all are good and even necessary. It’s not a question of the things being bad. It’s the assumption, the lie, the bubble, which elevates the acquisition of these good things for “I” above the provision of necessities for all.

So. How will we know if we’ve successfully convinced people of the lie that we don’t belong to one another?

Well…

If we were a society that believed in this way, we would likely find many people who began to believe that their ability to survive and thrive and prosper was entirely the product of their own effort and talent and ingenuity.

We’d begin to see people who equated their moral virtue with their own ability to survive. For those who thrive, prosperity would become indicative of a moral virtue greater than that of those who merely survive. The greater the prosperity, the greater the moral virtue.

We’d likely find many people who began equating wealth itself as interchangeable with moral virtue.

We’d likely find many people who began equating wealth itself as interchangeable with moral virtue.Which might result in more and more people becoming obsessed with accumulating more and more wealth, much more than they could ever spend, because at a very basic level, they seemed to believe it literally made them more virtuous. You might find others, not wealthy, who nevertheless began to believe this, and ascribe virtue to the wealthy simply for the fact of their wealth.

Which would result in an ever-increasing disparity in wealth. And anyone mourning the injustices endemic to this divide would be declared to be enacting some sort of class warfare, while those who sought to increase the disparity would do so specifically in terms of increasing virtuousness. In fact, the disparity itself would be defended as virtuous, while those calling for remedies would be thought of as divisive.

Protection of property would become more important than protection of humans in such a society. Protection of humans with property would become more important than protection of humans without property. Eventually, protection of the property would be seen as a primary goal of society, and protection of humans secondary. If property happened to be destroyed during a protest of the destruction of a human, the destruction of property would become the more shocking matter by far, and would be held up as an a priori negation of the rightness of the protesting organization's cause, whether that organization's members were responsible for the destruction or merely adjacent to it.

The ability of incorporated organizations to efficiently gather wealth might afford them greater protections and considerations under the law than that offered individual people. In time, those organizations might begin to be worshipped in subtle ways, their logos adorning the foreheads and chests and backs and feet of people loyal to their specific values, their leaders elevated to high priests. In time, the idea that these organizations should have greater protections and considerations under the law than human beings might become enshrined as received wisdom, simply for their outsized ability to generate wealth (which is, after all, a good thing).

The ability of incorporated organizations to efficiently gather wealth might afford them greater protections and considerations under the law than that offered individual people. In time, those organizations might begin to be worshipped in subtle ways, their logos adorning the foreheads and chests and backs and feet of people loyal to their specific values, their leaders elevated to high priests. In time, the idea that these organizations should have greater protections and considerations under the law than human beings might become enshrined as received wisdom, simply for their outsized ability to generate wealth (which is, after all, a good thing).The more the government of such a society became a matter of protecting and providing for property rather than people, the more the idea of community would give way to cynicism. The idea of government as being the mechanism by which humans choose to organize their shared life for common good would be replaced by ideas like this one: “The most frightening words in the English language are ‘I’m from the government and I’m here to help.’” Thus would our nation at last begin to be freed from the perceived tyranny of a coordinated response to a serious challenge.

Public good would become the necessary enemy of private good.

Public services would become the necessary enemy of private purchases.

The idea of tax collected for public values such as education or health would begin to seem monstrous, while the idea of large and powerful individuals and entities seeking relief from any contribution to the society in which they operate might be seen as pragmatic and necessary and even virtuous. After all, if wealth is the same as virtuousness, then tax is not how a shared life together is funded; it is not a price paid for the continuance of health and thriving within the society that has fostered your own health and thriving. Rather, it is the theft of your moral virtue, taken from you and given to unvirtuous people who, being unvirtuous, will surely waste it, and upon whom, given their unvirtuousnes, any investment is a immoral waste, no matter the outcome.

You might begin to hear people expressing the opinion that a society committed to ensuring basic physical needs for all people is engaged in slavery, while presuming that people toiling at jobs that do not provide wages enough to sustain life should stop their immoral complaining.

You might even begin to hear catch-phrases like ‘tax is theft.’

You might get a political party dedicated to only one discernible principle, that being the payment of as little tax as possible, the better to let the virtuous hold ever more of their virtue.

|

| 23 million uninsured in 10 years? Party time. |

The idea of tax collected upon an estate would begin to seem evil. The idea that the public should have some claim upon one’s virtue, rather than passing the full measure of virtue down the line of one’s own personal line of heredity, would seem like the gravest injustice.

|

| Cooooooooool. |

|

| Story here. |

If this were a deeply ironic universe, people might even fully believe all these propositions while worshiping within a religious tradition that taught there exists no greater danger to the soul than the love of money, no harder way to enter heaven than to make the attempt while encumbered with wealth.

If we were a society that believed we did not belong to one another, all these might be exactly the sort of thing we might see and hear.

This is the final conclusion: Other people do not matter.

|

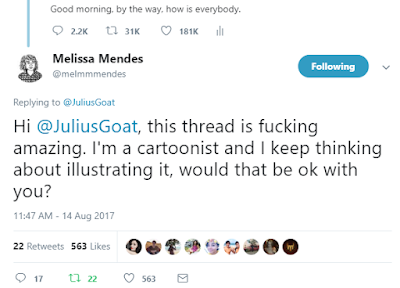

| Thread worth reading. |

|

| Seems like an important critique |

And here is the danger: Vulnerability. Living in a world where we do not belong to one another means living in a world in which others, resentful of their lost advantage, seeking for the phantom limb of it, will inevitably seek some scapegoat, and will inevitably land upon me. Living in a world where we do not belong to one another means living in a world where those who have best learned how to press a mean advantage will eventually consume their easiest victims, and will then, filled with greed's hunger, engorged with the virtues of wealth and power, turn at last to feast upon me.

When I choose to live in world in which other people do not matter, I choose to live in a world in which I will not matter, either.

0. ART

1. SISTER

2. THE GREAT DIVIDE

3. SPIRIT

4. BELONG

5. BUCKETS

6. THE KNIFE AND THE TRAIN

7. OUR FAVORITE FLAVOR

STORY

8. CHANGE THE LOCKS

9. THE LOWEST RUNG

10. BOTH SIDES

11. I’M TRYING, RINGO

12. EVERYTHING IS PERMITTED